The leaders faced players who had fewer points; therefore, the pursuers had every reason to push for a win to overtake those ahead of them. These considerations manifested themselves in the opening choices on almost all boards.

It is worth noting that among the trio of leaders, Andrey Esipenko had the best tie-break, followed by Hikaru Nakamura and Vidit Santosh Gujrathi.

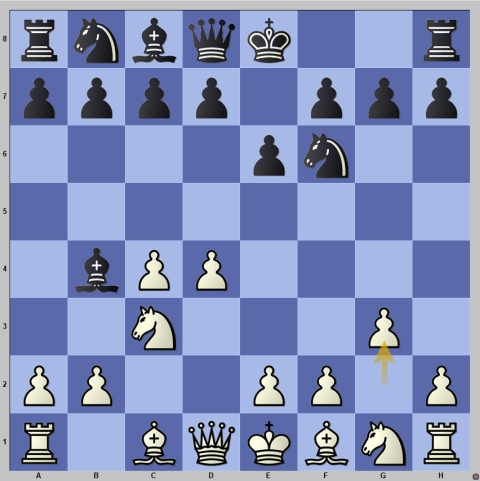

On board one, Arjun Erigaisi played 1.e4 against Hikaru Nakamura, and instead of his usual Berlin, Nakamura essayed the Kalashnikov variation in the Sicilian Defence, one of the sharpest choices in his repertoire.

He varied slightly compared to his usual choice in the Kalashnikov, though.

In this standard position, Nakamura had played 8…Rb8 on more than one occasion. In today’s game, he went for 8…Nf6, which is a transposition to the Sveshnikov variation where Black hasn’t played the move …b5, but rather …Be6. This is not considered optimal for Black, but it served the purpose of surprising Erigaisi, who started spending a lot of time.

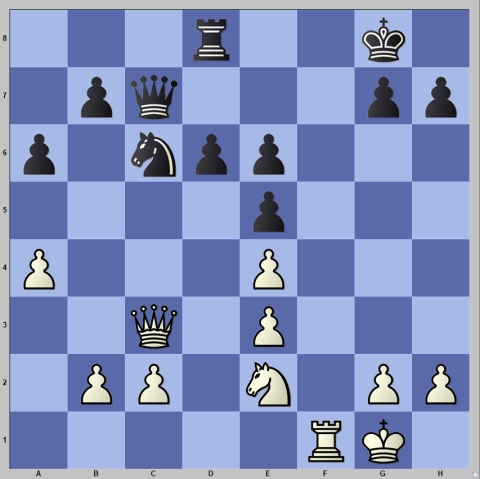

Nakamura’s surprise achieved its purpose, and White didn’t manage to pose serious problems. Black obtained a very comfortable middlegame with the initiative and had a half-hour advantage on the clock.

In this position, Black played 17…Qe7, but placing the queen on h6 would have been more incisive, putting pressure both on the knight on e3 and, indirectly, the pawn on c2. The pawn on d6 is taboo as Rxd6 allows …Bxe3 and White loses a piece or is mated after fxe3 Qxe3.

Nakamura’s choice allowed White to consolidate, but Hikaru still kept a little bit of something after he exchanged the knight on e3 and forced White to double the pawns.

White shouldn’t have problems holding this position in spite of the ugly pawns on the e-file, as they restrict the mobility of Black’s knight.

The queens were soon exchanged, and when Black played 33…Rb8 with the idea of …b6 to eliminate the pawns on the queenside, draw was agreed five moves later.

On board two, there was an intense internal struggle visible on Vidit Santosh Gujrathi’s face as he pondered his choice on move seven.

Alexandr Predke chose the solid Queen’s Gambit Declined and in the usual tabiya arising from this opening, Vidit spent 10 minutes deciding whether to go for a safety-first approach by transposing to an endgame with 7.dxc5 or to choose something else that would keep the queens on the board.

After ten excruciating minutes, Vidit chose the former option. This didn’t necessarily mean that he was ready to draw, but this choice did set the calmer course of the game he wanted to play. On the other hand, playing an endgame against a ferocious attacker like Predke was perhaps not a bad idea. It turned out to be very important later on.

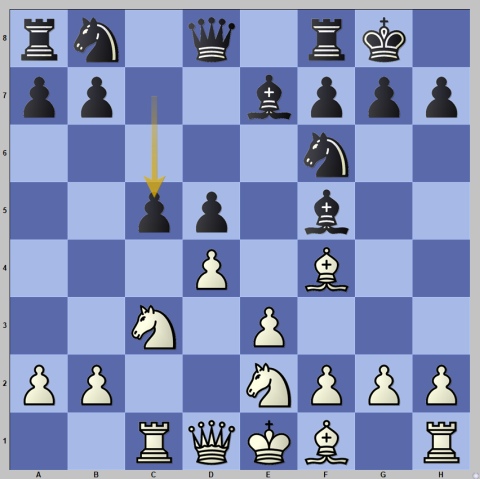

The QGA endgame is a calm affair, so both sides comfortably finished development. Perhaps unable to control his impulses and true to his active style, Predke advanced on the kingside with 15…g5.

White replied with 16.Nfd4 Nxd4 17.Bb4 (a zwischenschach to worsen the position of Black’s king) Ke8 18.Nxd4, but the position remained balanced after 18…g4.

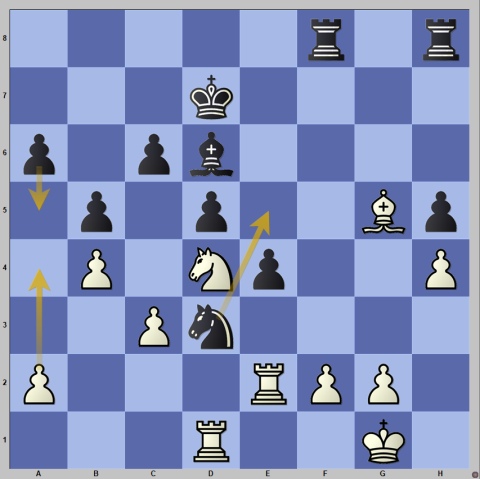

In the ensuing play, Black was a bit imprecise and allowed White to gain some momentum thanks to the maneuver Nb3-c5.

Black should have eliminated the knight, and while White’s bishop pair would certainly have given him a good reason to play for a long time, but Predke would have kept decent drawing chances.

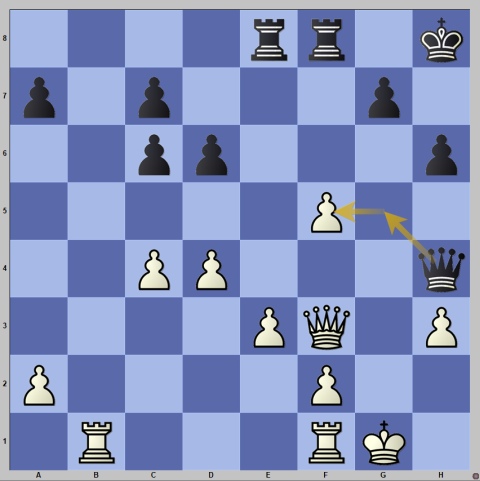

Predke, again, chose the way of complications with 20…Bc6.

Objectively, this move gives White an advantage, but the narrow path leading to it is incredibly well hidden.

After the critical 21.Nxa6! Bf3 22.Rxd8 Kxd8 White has to find the stunning 23.h4!! (an idea that Vidit actually saw during the game!)

The idea of the move is to chase away the rook from the fifth rank so the white knight can escape via c5, or in case of 23…Bxe2 24.hxg5 Nd5 24.Bc5 Bxa6 25.Bxb6 Nxb6 26.Kh2! White has better chances in the endgame as Black’s kingside is weak. Incredibly complicated and deep stuff!

After 21.Nxa6 Predke didn’t go for these lines and played 21…Nd7, trying to trap the knight on a6.

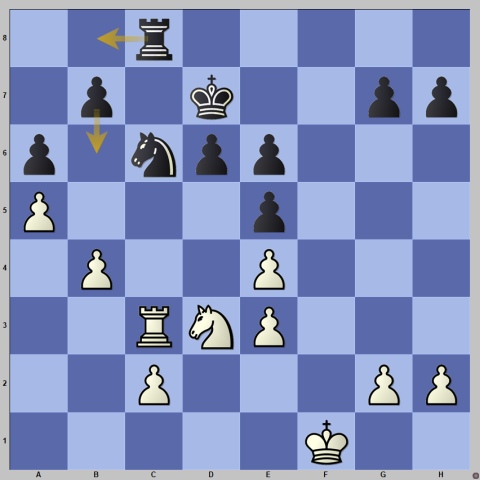

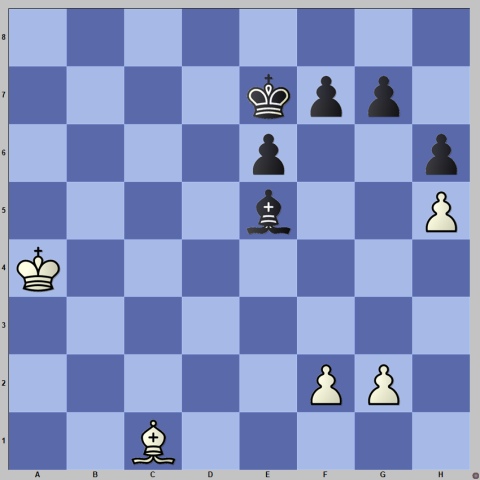

In the ensuing complications, White managed to keep his extra pawn and reach a technical endgame with excellent winning chances.

Black cannot regain the pawn by taking on a2 because it fails to Bb5, winning the d7-knight.

Vidit made most of the winning chances and in fact converted in an incredibly smooth fashion!

This win brought Vidit the victory in the FIDE Grand Swiss and a spot in the Candidates tournament! It was an incredibly impressive performance by the player who lost in the first round and didn’t really believe in a comeback, but he fought every single day and was awarded for his fighting spirit.

On board three, Anish Giri was very motivated to win against the leader Andrey Esipenko, as that would have given him extra FIDE Circuit points, his possible path to Toronto. However, Esipenko demonstrated excellent opening preparation to neutralise Giri’s 1.d4.

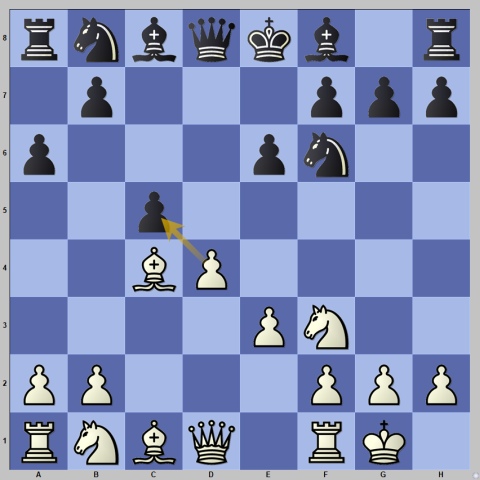

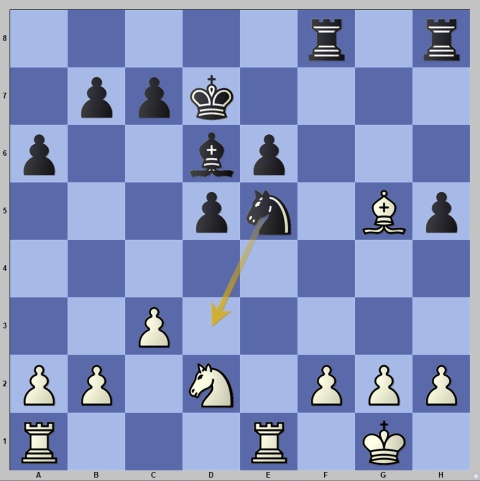

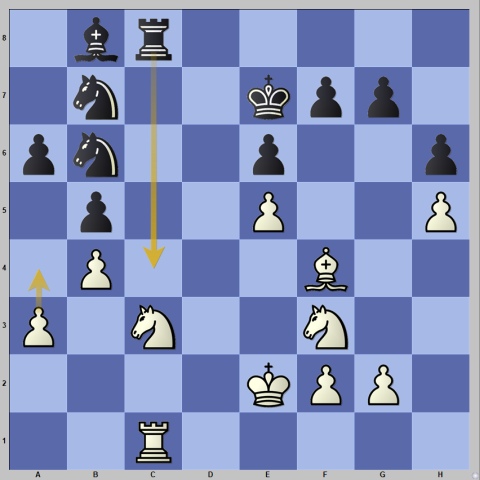

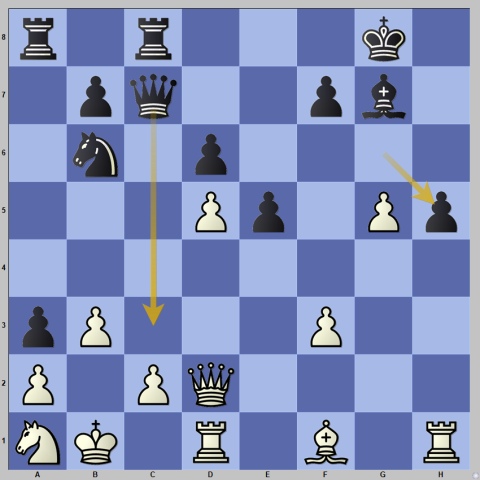

Esipenko chose the Queen’s Gambit Declined, and Giri went for the Exchange variation. Then, on move eight, Esipenko played a move that on first sight, appeared like a blunder.

Black’s last move was 8…c5 and after 9.dxc5 Bxc5 10.Nxd5 Nxd5 11.Rxc5 White won a pawn. Esipenko’s preparation went much deeper, and he blitzed it out until move 15.

Black is a pawn down, but he has a development advantage, and in cases where players go for such lines, it means that they had analysed them to exhaustion, i.e., to a draw.

However, something odd happened in this position. Giri played 16.f3, and in despite being one of the top engine’s choices, this move sent Esipenko thinking. Upon 18-minute reflection, he played 16…h5, a possible move, one of the several moves that the engines like. Then after 17.Rxb7 Esipenko spent further 34 (!) minutes and opted for a sub-optimal 17…Rd4?! instead of the correct 17…Rac8! with the threat of 18…Nd5, which offers great compensation.

Giri responded with 18.Be2, and it turned out that Black didn’t have enough for the two pawns. A very strange case of suddenly forgetting one’s preparation and immediately ending up in a bad position after failing to figure things out over the board.

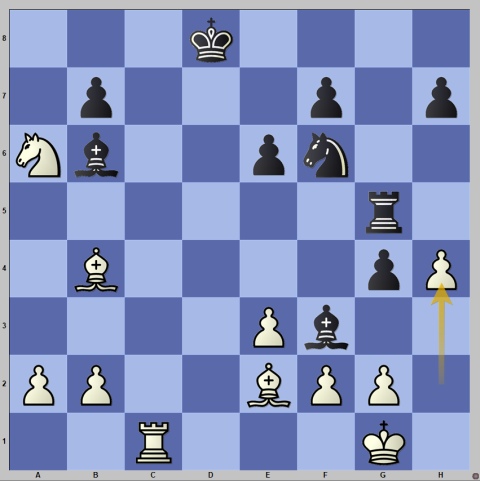

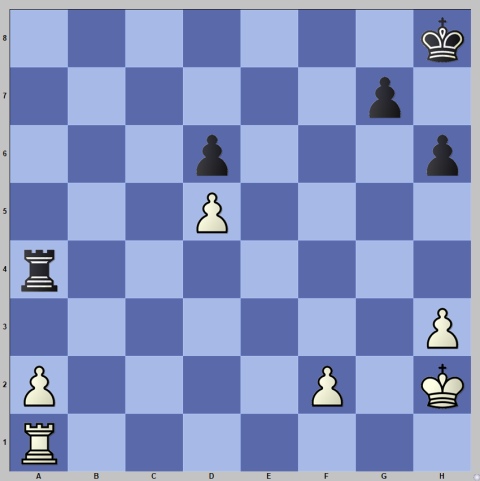

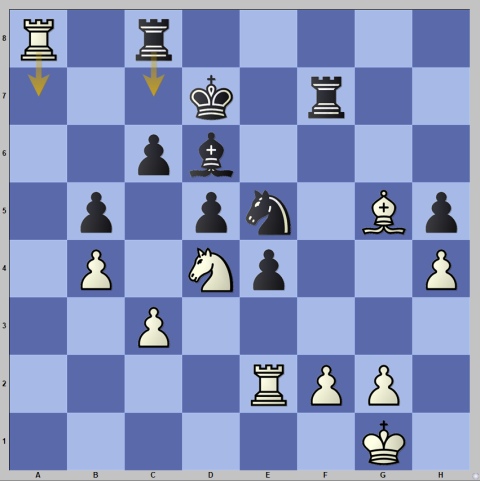

Esipenko somehow managed to limit the damage and transposed to a gloomy endgame a pawn down. His only comfort was that White’s extra pawn was a doubled one on the f-file.

In this position, Black missed the last chance to put up more serious resistance. He should have played 24…Ra2, in order to tie White down to the defence of the pawn on b2.

Andrey played 24…Rc8? instead and after 25.Rd4 gave up a second pawn in search of counterplay with 25…Rc2. Unfortunately for him, there was nothing to find. Giri picked up the pawn on b4, protected his kingside with g3 and won on move 33.

A painful defeat for Esipenko, who will miss out on the Candidates, and a very important win for Giri who improved his FIDE Circuit standings to overtake Gukesh.

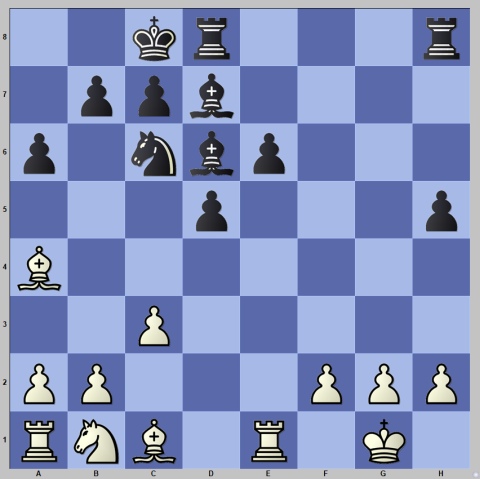

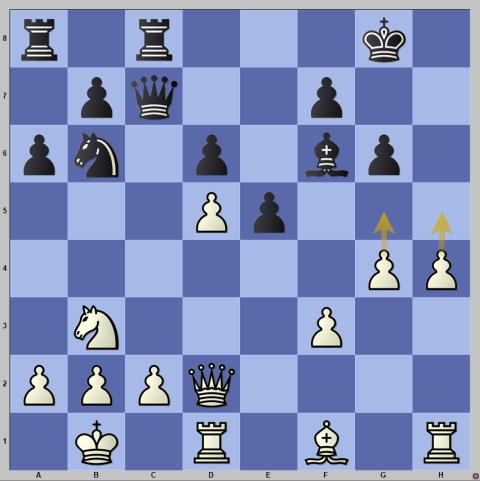

On board four Fabiano Caruana sprung an early surprise in his game against Vincent Keymer. In the Nimzo-Indian, he chose the half-forgotten Romanishin variation with the move 4.g3.

This variation was very popular in the 1980s when it was very effectively used by Kasparov in his matches with Karpov. Kasparov usually started with 4.Nf3, and after 4…c5 played 5.g3. The non-standard positions were uncomfortable for Karpov, and thanks to the wins in this line, Kasparov won the World Championship title in 1985.

Caruana’s 4.g3 allows for some additional choices, and Keymer picked one of them by taking on c3 immediately, followed by …d6.

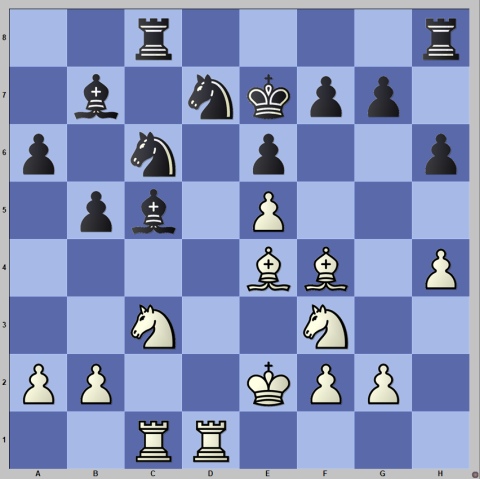

The game quickly left theory, and a complex middlegame position appeared on the board.

With his last move, White posed serious problems as he intended Nf5 and/or f4, starting an attack on the kingside. Black found the correct reply 13…h6! which invited simplifications as the way of securing his kingside.

The minor pieces were exchanged rapidly after 14.Bxf6 Qxf6 15.Bxe4 Qxe4 and later on, White also traded his bishop for the knight on c6.

The ensuing position with only heavy pieces on the board was equal.

White has a compact pawn mass in the centre, but his king is weaker. Black regained the pawn with 20…Qg5xf5 and had more than enough activity to hold the draw in the double-rook endgame, which later became a rook endgame. After move 30, it was obvious that the activity of the black rook, coupled with the weaknesses of White’s pawns, made the position an easy draw.

FIDE Grand Swiss final standings:

1. Vidit – 8.5 points;

2. Nakamura – 8;

3-7. Esipenko, Erigaisi, Keymer, Maghsoodloo and Giri – 7.5

In the women’s section, Batkhuyag Munguntuul had to play for a win against leader Rameshbabu Vaishali for two reasons: one was a grandmaster norm, and another was a possible qualification in the Candidates. For Vaishali, a draw would secure a victory in the tournament.

Therefore, it was surprising to see Vaishali choose a sharp line in the opening.

Instead of developing quietly with 7…Be7 or 7…g6 Vaishali went for 7…h6 followed by …g5.

The surprise worked wonders for Vaishali as soon enough, White committed a serious mistake.

White had to play 12.d5! Ne7 13.Bxd7 Kxd7 14.Rb4 with the idea of Rxb7 or Qa4, with good compensation.

Instead, she played 12.dxe5?! but after 12…0-0-0! Black got an advantage thanks to her pawn preponderance in the centre after the exchange of queens.

A dream scenario for Vaishali and a very dispiriting start for Munguntuul.

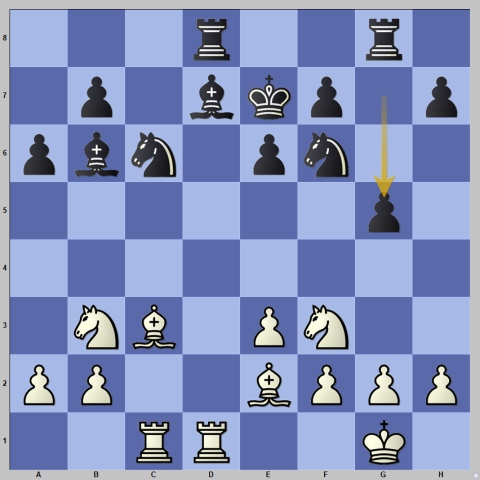

Black continued naturally, centralising her knight and using the semi-open files on the kingside for her rooks. By move 20, she had a comfortable advantage.

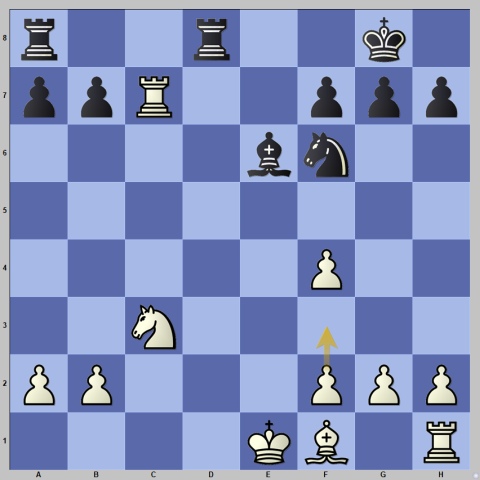

Next, Black played …Nd3 and followed up with …e5-e4. This allowed White to establish some sort of blockade, but Black was clearly better.

In this position, Black should have played 26…a5 in order to prevent White’s counterplay. After 26…Ne5?! chosen by Vaishali, White played 27.a4! and suddenly Batkhuyag had counterplay on the queenside. By this point, both players were in serious time trouble, with seven (for White) and four (for Black) minutes to reach move 40.

Black erred further with 27…Rf7?! and after the natural 28.axb5 axb5 29.Ra1 Rameshbabu was now on the defensive!

Luckily for her, after White penetrated along the a-file and Black defended by …Rc8. Munguntuul started to repeat moves with Ra8-a7, with Black replying …Rc8-c7.

White could have continued the game with Rea2 but instead decided to claim a draw.

With this draw, Vaishali won the FIDE Grand Swiss!

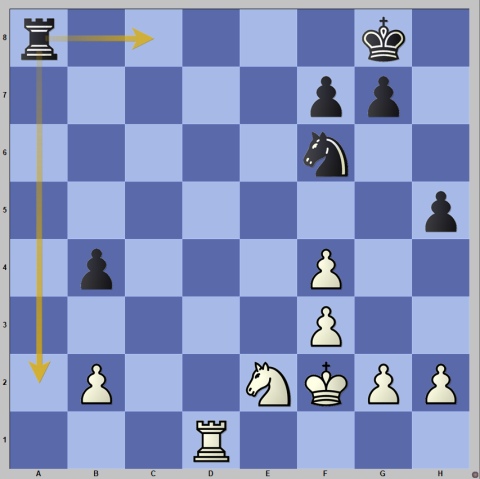

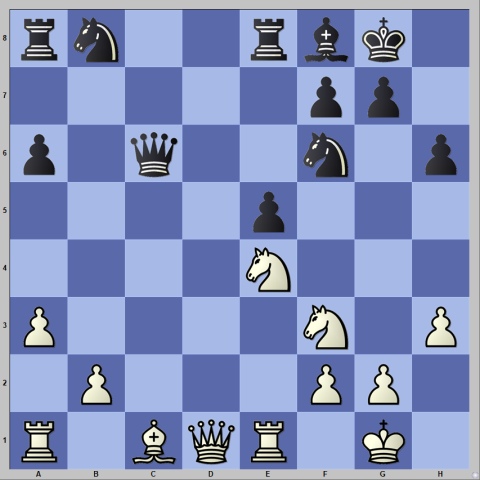

On board two, Pia Cramling went for an early exchange of queens in her game against Anna Muzychuk. A true legend, Cramling is known for her Karpov-like style and in this game, where she needed to win in order to keep some chances for qualification for the Candidates, she went for what she does best – play endgames.

In the Semi-Slav, White went for the line with 5.Qd3, and after the main response for Black against this line, the queens were exchanged on move 10.

Both sides finished development and reached an equal endgame.

The endgame is objectively fine for Black, but with all the pieces except the queens, a lot of play could be expected.

In order to create some play, White advanced the h-pawn to h5 and expanded on the queenside, but Black patiently maneuvered and exchanged pieces.

By move 22, White couldn’t boast of any progress. Perhaps a bit frustrated, here Pia miscalculated with 23.a4? because after 23…Rc4! White was losing a pawn. To her credit, Cramling managed to compose herself and found a sequence of moves that eliminated all the pawns on the queenside and led to a pawn-down but drawn bishop endgame with all the pawns on one wing.

White didn’t have problems holding the draw, which was agreed on move 41. With this draw, Muzychuk secured clear second place.

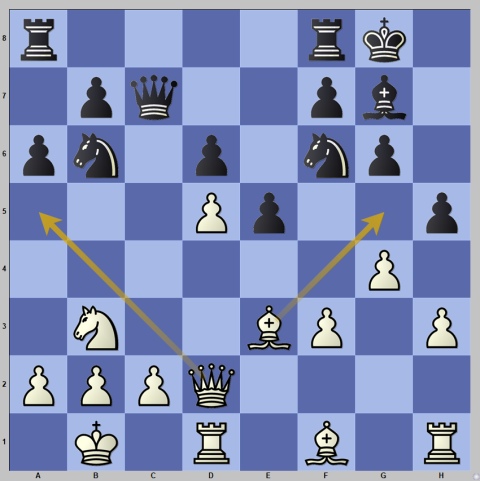

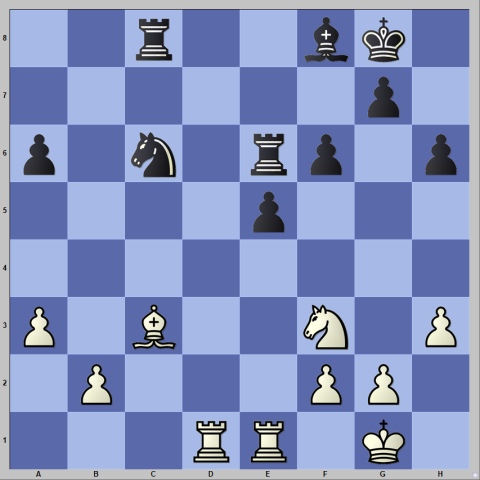

On board three Tan Zhongyi met Gunay Mammadzada’s Najdorf with the English Attack. In a well-known theoretical position, she played a move that had been tried only twice in computer games.

White’s usual continuation here is 16.Qa5, but Tan Zhongyi played 16.Bg5!?, a move that posed serious practical problems. Black’s best way to react to it is the difficult move 16…e4!?, sacrificing a pawn to open the long diagonal for the dark-squared bishop.

Black was obviously on her own in this position and, after 12 minutes, decided to sacrifice another pawn with 16…h4 in order to slow down White’s kingside attack. However, this was only temporary as after 17.Bxh4 Rfc8 18.Bxf6 Bxf6 19.h4 White was on the verge of opening files on the kingside after g5 and h5.

Both players pushed pawns against their opponent’s king, and the critical position arose on move 22.

Black’s last move 22…gxh5? was a mistake. She had to play 22…Qc3, stopping White’s c4. White also didn’t immediately realise the importance of pushing c4 and played 23.Bh3? when 23.c4 would have secured her position. Black missed the second chance to play 23…Qc3, which here would even have given her a winning advantage in view of the vulnerability of White’s pawns on f3 and d5 in the endgame after the exchange of queens. She erred with 23…Rf8? And White finally played 24.c4 with a dominant position. Black’s attempt to open the long diagonal with 24…e4 25.fxe4 gave little because Black couldn’t create threats along the long diagonal.

White successfully plugged the long diagonal and got a winning advantage. Black had the unenviable choice of exchanging queens with a lost endgame or sacrificing the knight on b6 for no compensation. To make things even worse for Black, she had only six minutes for 13 moves.

Her resistance didn’t last long, and White won in 34 moves. This victory ensured Tan Zhongyi’s participation in next year’s Candidates tournament!

On board four, Stavroula Tsolakidou faced the Zaitsev variation in the Ruy Lopez in her game with Antoaneta Stefanova.

White didn’t choose a critical line and allowed Black to equalise by executing the liberating …d5 push. After 20 moves, Black didn’t have any problems.

After the correct play by both sides, the queens were exchanged, and the evaluation was still the same: equality.

Despite Stefanova’s usual time trouble, the position was simple enough to avoid serious mistakes. After the opponents reached the time control, a draw was agreed on move 43.

FIDE Women’s Grand Swiss final standings:

1. Vaishali – 8.5 points;

2. Anna Muzychuk – 8;

3-4. Tan Zhongyi and Munguntuul – 7.5 points;

5-8. Garifullina, Stefanova, Cramling and Mariya Muzychuk – 7 points

The closing ceremony and the prize giving of the FIDE Grand Swiss took place after the last game of the tournament finished.

It started with a short address by FIDE CEO Emil Sutovsky, who called the tournament “thrilling” and full of “fantastic chess.” He thanked the organisers, Chief Organiser Alan Ormsby and everybody involved in the event. He congratulated the winners, Vaishali and Vidit, on their phenomenal performance, the norm winners and the players who qualified for the Candidates and the FIDE Grand Prix.

After Sutovsky’s speech, the winners were called to the stage for photos and congratulations.

Chief Organiser Alan Ormbsy thanked the arbiters, the staff at the Villa Marina and everybody involved in the tournament. He thanked the players and expressed satisfaction at the close cooperation with FIDE. He announced that with the help from the Scheinberg family, there is a good chance that in two years, the Isle of Man will organise the Grand Swiss again.

The ceremony concluded with a buffet and beverages for everybody present and continued with informal chess games and relaxed conversations.

Written by GM Alex Colovic

Photos: Anna Shtourman

Official website: grandswiss.fide.com

More Stories

Gukesh: Today was a good day!

Ding Liren takes down Gukesh in the first game of title match

Ding Liren takes down Gukesh in the first game of title match

2024 FIDE World Championship: Gukesh draws White in the first game

Chess stars come to New York for the strongest chess tournament in U.S. history

World Senior Championship 2024 starts in Porto Santo, Portugal