The draws on the top boards allowed Hikaru Nakamura to join the leaders as the only player to win in the upper echelon. The game of the round was undoubtedly the insanely complex battle between Alireza Firouzja and Hans Niemann. Black had excellent winning chances, but in mutual time trouble, he missed them. In the derby of the women’s section, Bibisara Assaubayeva turned things around after falling into a strategically lost position after the opening. This victory made her the sole leader in the Women’s Grand Swiss.

In the fifth round of the FIDE Grand Swiss, the leader of the tournament faced the top seed on board one.

Andrey Esipenko was surprised in the opening by Fabiano Caruana’s move-order after 1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 e6 3.Nf3 a6!?

The point of this a-pawn move is to avoid the Catalan. In case White continues with 4.g3, then Black has the option of 4…b5!?, a move that was recently played by Hikaru Nakamura.

Esipenko continued along the usual lines with 4.Nc3, and after 4…d5, we had a transposition to the line Caruana played in Round 3 against L’Ami.

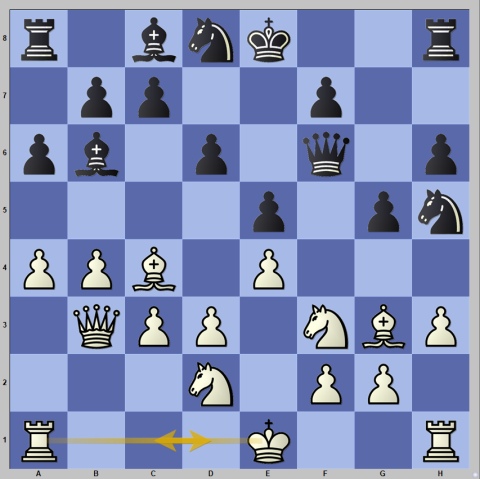

Perhaps to avoid possible surprises, Esipenko sprung his own surprise a few moves later. In the tabiya of the line with early …a6 he played a mysterious king move.

In this position, White usually chooses among 10.Bf4, 10.Qc2 and 10.h3, but Esipenko came up with a somewhat abstract move 10.Kh1!? with some ideas of pushing the g-pawn or/and safeguarding against accidental checks on h2 or along the g1-a7 diagonal if White opens it by pushing f3 and e4 or f4. Still, the main advantage of the move was to sidestep the mainstream theory.

On his next move, White tried to expand on the kingside with Nd2 and f4, which Caruana prevented by pushing …h6 and …g5. In a complex middlegame, both opponents played well, and after a series of exchanges, the draw was agreed by perpetual check on move 42.

On board two, Hikaru Nakamura was luckier than Esipenko – his opponent Alexey Sarana didn’t prevent him from playing the Catalan. As is his habit early in the game (which makes him one of the trickiest players when it comes to opening preparation), Nakamura introduced an early „twist“ by playing the sideline 8.Bc3 (compared to the more popular 8.Qc2, 8.Qb3, 8.a4, 8.Bf4).

Black continued with 8…b6, and after 9.cxd5, he took on d5 with the pawn, unlike Magnus Carlsen, who, in his blitz game against Ding Liren in 2017, captured with a knight, keeping the long diagonal open.

Soon enough, the position took Queen’s Indian shape where Black creates some activity in the centre with …c5, but his bishop on b7 is rather passive.

In the complex middlegame, the position with Black’s hanging pawns on c5 and d5 arose. White tried to put pressure on them while Black had free-piece play thanks to the space those pawns provided.

In this critical position, Black pushed the wrong pawn. Correct was 18…c4! 19.Nd4 Rfd8, when the nice blockading knight prevents White from attacking the pawn on d5.

Sarana went for 18…d4?! and after 19.Bxb7 Qxb7 20.Rc4 White got a chance to concentrate his pieces against the c5-pawn.

Another positional mistake by Black was to offer the exchange of bishops, which removed the best defender of the c5-pawn. After that, the pawn on c5 was doomed, and White won it.

However, Nakamura wasn’t perfect in the conversion phase.

White should have transferred the knight via e1 to f3, but instead, he went for 29.Nc5? allowing 29…Qh3 (or 29…Qg4 or even 29…Rxc5! 30.Rxc5 hxg3 31.hxg3 Nf4! with equality) and suddenly Black had sufficient compensation.

However, Alexey missed several good chances and lost the d4-pawn. Sarana regained one pawn by taking on b2, but after the exchange of queens, he lost the far-advanced pawn on h3.

Nakamura converted the two-pawn advantage in a long knight endgame with patient play.

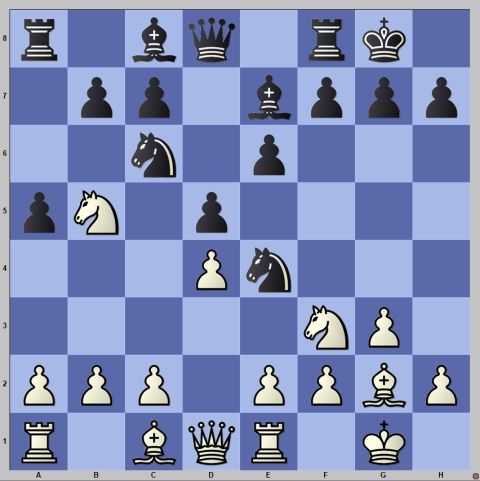

On board three Alireza Firouzja played the King’s Indian Attack against Hans Niemann, but just like Nakamura, he introduced a little twist early on.

In this standard position, White usually plays 6.Nbd2, with the intention to push e4, but Firouzja opted for 6.Re1!?. The move also prepares e4, but not immediately, as White first wants to develop with Bf4 or Nc3, for example.

Niemann responded with 6…Nc6, intending …e5, to which Firouzja changed the structure by preventing it with 7.d4. The opponent stepped into uncharted territory soon enough as after 7…a5 8.Nc3 Ne4 9.Nb5, the position was already very original and new.

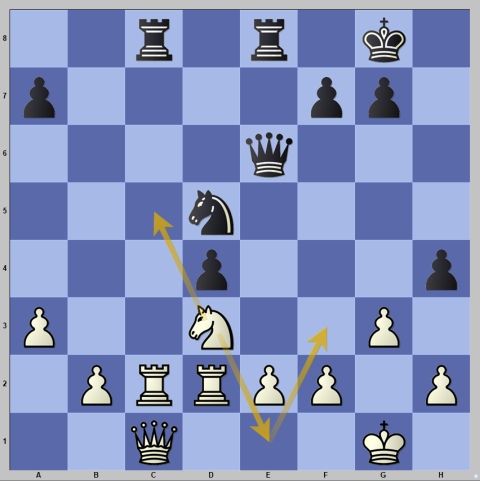

The game left the safe territory when, on move 16, Niemann sacrificed two pieces for a rook and a pawn.

He played 16…Nxf2!? 17.Rxf2 Bxf2 18.Kxf2 Qxf6 19.Kg1 Qxb2 when the game became a big mess.

Objectively, the position was balanced, but it was easier to play with Black since he had the safer king and White’s pieces lacked coordination.

Both players entered severe time trouble, and this affected the quality of their moves. There were some difficult decisions to be made with very little time on the clock.

It looks very dangerous for White, but in fact, he can stay afloat with 26.Ba6 or 26.Nd2. Firouzja went for 26.Qd2? which should have lost after 26…Qxc4 27.Qxd7 and now 27…Rfe8! was the killer blow. Niemann missed it and went for 27…Re2? after which the position was equal again.

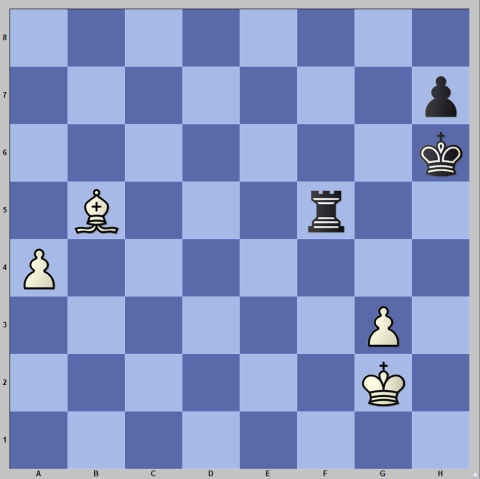

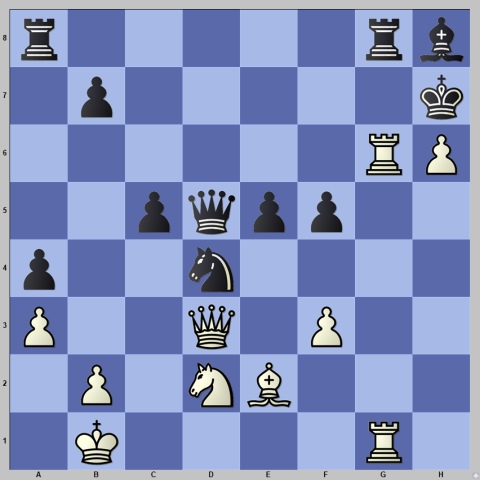

The engine indicates the move 28.Rc1! when the complications continue. He didn’t find this move, and after the natural 28.Bxc6 a forcing variation after 28…Qc5 29.Kh1 Qf2 30.Qh3 Re1 31.Rxe1 Qxe1 and the subsequent exchange of queens (which was premature, as Black should have kept the tension by playing …a3) on f1 led to Black winning the pinned bishop with …g5. White won the pawn on a4, and then after the time control, the following endgame appeared.

This position is objectively a draw, and Firouzja managed to prove it.

A wild game!

On board four, Javokhir Sindarov and Yu Yangyi tested a long theoretical line in the Petroff. They followed a game by Sindarov played only a month prior to this tournament, a game he won against Bu Xiangzhi. Yu Yangyi deviated from the play of his compatriot by introducing a novelty on move 16 and quickly equalized.

In the Evans Gambit, where Black doesn’t take on b4 and plays …Bb6 the position resembles modern-day Giuoco Piano. There is a game by Paul Morphy against Samuel Boden from 1858 where, in this type of position, he played not one, but two modern ideas.

Here, Morphy played 9.Bg5. The pin on the knight is a very popular ploy in modern chess, often used by Magnus Carlsen, not only in the Giuoco Piano, but also in the Ruy Lopez.

A few moves later, Moprhy played an original idea that still hasn’t caught up, but perhaps after the game shown below, this will change.

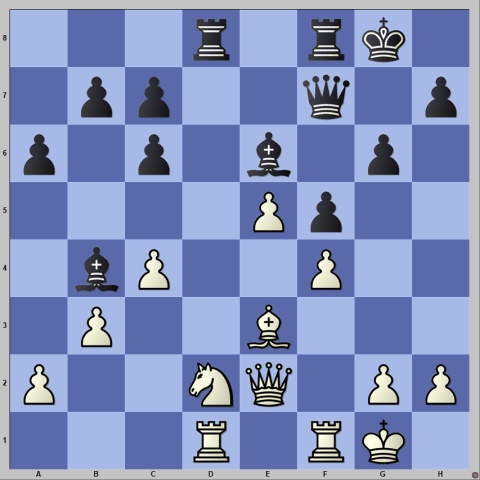

In this position, Morphy played 14.0-0-0!?.

Rameshbabu Praggnanandhaa played the Giuco Piano against Sandro Mareco. In the position below, we already have the pin on the h4-d8 diagonal.

Can you guess White’s next move?

10.0-0-0! of course! Did he know about this historic parallel?

Like the great Morphy, Praggnanadhaa sacrificed material for an attack. The engines easily refuted it, but Mareco had to solve serious problems over the board. After some imprecisions, White obtained enough compensation for the pawn, plus Black was in serious time-trouble.

Mareco returned the pawn and managed to exchange queens, thus eliminating the danger of an attack on his king. The endgame they reached was drawn.

In the women section on board one Tan Zhongyi countered Bibisara Assaubayeva’s King’s Indian Defence with Petrosian’s Variation. However, instead of Petrosian’s pin with Bg5, she used the modern treatment with h3.

These lines are considered quite difficult to play for both sides as they require a deep understanding of which positions are acceptable and which are not. Both players made some inaccuracies, but when the position stabilized, it was White who had a stable advantage.

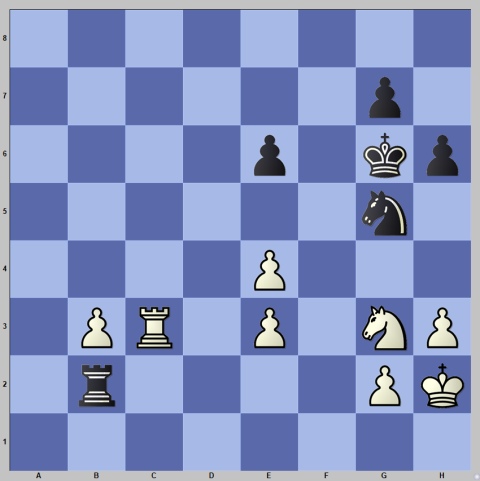

White’s dominant knight on d5 and Black’s very bad bishop on g7 determine White’s advantage.

However, instead of strengthening her position with the manoeuvre Nb1-c3, Tan Zhongyi was tempted by a kingside advance, but this weakened her grip in the centre.

Black transferred her knight via c7 and e6 to d4, and after Tan erroneously took on f5, this turned the tables completely, as White had no attack while Black took over the centre.

The difference between the two diagrams is stark.

Black also took over the g-file, penetrated with her rook on g3, pushed …e4 and wrapped up the game.

On board two Rameshbabu Vaishali decided to repeat the Delayed Exchange Variation in the Ruy Lopez from the game Anna Muzychuk played in round three against Irina Bulmaga. She had a different idea this time as, unlike Bulmaga, she didn’t go for an early opening in the center but chose a slower setup with d3. However, when Black provoked the d4-push by putting a knight on c5, Vaishali changed her plans and opened the centre.

This led to a position that can arise in the Berlin endgame – White had a protected passed pawn on e5, but Black’s light-squared bishop safely blockaded it.

These positions are considered very safe for Black and usually lead to a draw as neither side can make progress. The game did not change this evaluation.

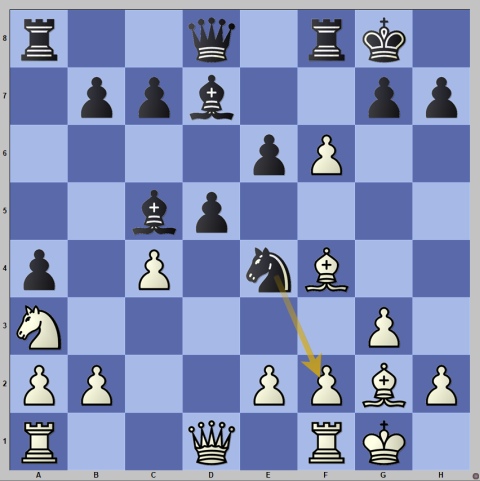

Aleksandra Goryachkina is usually a 1.d4 player, but recently, she has started experimenting with 1.e4. Against Meruert Kamalidenova she opted for 1.e4 and met her opponent’s Sicilian after 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 with 5.f3, a move that famously secured Magnus Carlsen the victory in the tie-break of his World Championship match against Sergey Karjakin in 2016.

The idea is to establish a Maroczy Bind with c4 and keep the position under control, not allowing the standard Sicilian counterplay.

Black tried to break the bind by pushing …f5, but White emerged better thanks to her control of the light squares.

Black’s last move 20…Bd2? was bad, but it took a keen eye to notice the refutation 21.c5! which Goryachkina played. White opens the position, and the unopposed light-squared bishop becomes particularly dangerous.

Meruert took 21…dxc5 (it was more resilient to take with the b-pawn, though after 21…bxc5 22.Rad1 followed by Nxb4 White has a big advantage) and after 22.Nxe5 White had a decisive advantage as the control of the light squares, and her better coordination were the key factor. Goryachkina was precise in converting her advantage.

On board four Batkhuyag Munguntuul chose a quiet line against Antoaneta Stefanova’s Ruy Lopez. The game progressed in a slow, manoeuvring fashion, where the only dynamic factor was the upcoming time-trouble.

Time-troubles are nerve-racking and since White had a little more time, it made it a little easier to play for her. Eventually, Batkhuyag won a pawn, but it was a doubled e-pawn going nowhere, plus Antoaneta had enough counterplay with her active rook.

Even winning a second pawn, a passer one on the b-file, wasn’t enough for White, as Black’s pieces didn’t allow White to untangle.

White tried to give up the b-pawn to remove the black rook from the first rank, but that didn’t improve her chances. Black held the draw rather comfortably.

Nakamura’s win was the only one on the top boards. With this victory, he joined the leader Esipenko. The „density“ of the tournament makes it so difficult to win a game, and with every round, the players tend to be more and more cautious. Assaubayeva is leading alone, but the chasing pack consisting of Vaishali, Anna Muzychuk and Goryachkina won’t leave her at peace.

Fans can follow the Grand Swiss 2023 by watching live broadcasts of the event on FIDE Youtube and Twitch with expert commentary by GM David Howell and IM Jovanka Houska.

Round 5 starts tomorrow at 14:30 PM local time.

Written by GM Alex Colovic

Photos: Anna Shtourman, John Saunders

Official website: grandswiss.fide.com

More Stories

Full list of participants for 2024 WRB announced

Gukesh D crowned 18th FIDE World Champion

FIDE World Championship Game 14: Gukesh D crowned 18th World Champion

FIDE World Championship Game 11: Ding collapses under pressure as Gukesh takes the lead

FIDE World Championship Game 9: The calm after the storm

Full list of participants for 2024 WRB announced